- Home

- Georges Feydeau

Plays 2

Plays 2 Read online

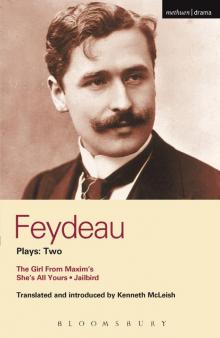

Georges Feydeau Plays: Two

The Girl From Maxim’s, She’s All Yours, Jailbird

Feydeau was the most successful French dramatist of the belle époque and is now widely regarded as one of the greatest of farce-writers and a worthy successor to Molière and Labiche. His series of dazzling hits matched high-speed action and dialogue with ingenious plotting. Reaching the heights of farcical lunacy, his plays nevertheless contain touches of barbed social comment and allowed him to mention subjects which would have provoked outrage in the hands of more serious dramatists. This volume of new, sparkling translations by Kenneth McLeish contains two plays from the peak of his career, The Girl from Maxim’s, perhaps his best known, and She’s All Yours (La Main passe), together with an early work, Jailbird (Gibier de potence).

Georges Feydeau was born in Paris in 1862, the son of the novelist Ernest Feydeau. His first one-act play, Love and Piano, was performed when he was 18 and he had his first success with Tailleur pour dames in 1887, when he also married an heiress. Among his many plays his best known are perhaps Le Système Ribadier (1892), Monsieur chasse! (1892), Un Fil à la patte (1894), L’Hôtel du libre échange (1894), Le Dindon (1896), La Dame de chez Maxim (1899), La Puce à l’oreille (1907), Occupe-toi d’Amélie (1908), and On purge bébé (1910). He contracted syphilis and was committed to an asylum in 1919 and died in 1921.

by the same author

FEYDEAU PLAYS: ONE

(Heart’s Desire Hotel, Sauce for the Goose, The One That Got Away, Now You See It, Pig in a Poke)

Contents

Chronology

Introduction

THE GIRL FROM MAXIM’S

SHE’S ALL YOURS

JAILBIRD

Georges Feydeau Chronology

1862

Born in Paris, December 8

1874

Death of father, Ernest

1871–9

Attended boarding schools

1879

Joined a law firm as clerk

1880

Began to write and recite monologues

1881

Par la fenêtre (Through the Window), first play to be professionally performed, produced by Rosendaël

1883

Amour et piano (Love and Piano), Théâtre de l’Athénée Took post as secretary to Théâtre de la Renaissance

1883–4

Military service

1884

Gibier de potence (Jailbird), produced by Le Cercle Volney

1887

Tailleur pour dames (Tailor to the Ladies), Théâtre de la Renaissance – his first hit

La Lycéenne (The Schoolgirl), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1888

Un Bain de ménage (A Household Bath), Théâtre de la Renaissance

Chat en poche (Pig in a Poke), Théâtre Déjazet

Les Fiancés de Loches (The Fiancés of Loches), Théâtre Cluny

1889

Married Marianne Duran

L’Affaire Edouard (The Edward Affair), Théâtre des Variétés

1890

Le Manage de Barillon (Barillon’s Marriage), Théâtre de la Renaissance

1892

Monsieur chasse! (The One That Got Away), Théâtre du Palais-Royal

Champignol malgré lui (Champignonl in Spite of Himself), Théâtre des Nouveautés

Le Système Ribadier (Now You See It), Théâtre du Palais-Royal

1894

Un Fil à la patte (On a String), Théâtre du Palais-Royal Le Ruban (The Ribbon), Théâtre de l’Odéon

L’Hôtel du libre échange (Heart’s Desire Hotel), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1896

Le Dindon (Sauce for the Goose), Théâtre du Palais-Royal

Les Pavés de l’ours (A Little Bit To Fall Back On), Théâtre Montpensier, Versailles

1897

Séance de nuit (Night Session), Théâtre du Palais-Royal Dormez, je le veux! (Sleep, I insist!), Théâtre de l’Eldorado

1899

La Dame de chez Maxim (The Girl From Maxim’s), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1902

La Duchesse des Folies-Bergères (The Duchess From the Folies-Bergères), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1904

La Main passe (She’s All Yours), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1905

L’Age d’or (The Golden Age), Théâtre des Variétés

1906

Le Bourgeon (The Bud), Théâtre du Vaudeville

1907

La Puce à l’oreille (A Flea In Her Ear), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1908

Occupe-toi d’Amélie (Look after Lulu), Théâtre des Nouveautés

Feu la mère de Madame (Madame’s Late Mother), Théâtre de la Comédie Royale

1909

Moved into the Hôtel Terminus, where he lived until 1919

Le Circuit (The Circuit), Théâtre des Variétés

1910

On purge bébé (Purging Baby), Théâtre des Nouveautés

1911

Cent millions qui tombent (A Hundred Million Falling), Théâtre des Nouveautés

Mais n’te promène donc pas toute nue! (Don’t Walk Around Naked!), Théâtre Fémina

Léonie est en avance (Léonie Is Early), Théâtre de la Comédie Royale

1913

On va faire la cocotte (We’re going to play cocotte), Théâtre Michel

1914

Divorced

Je ne trompe pas mon mari (I’m Not Deceiving My Husband), Théâtre de l’Athénée

1916

Suffered increasing bad health caused by syphilis Hortense a dit: ‘Je m’en fous! (Hortense said: ‘I don’t care!’),

Théâtre du Palais-Royal

1919

Committed to a sanatorium by his family

1921

Died June 5

Introduction

Feydeau’s father, Ernest Feydeau, was a stockbroker and novelist, a friend of Baudelaire, Flaubert and the Goncourt brothers – who mocked him in their Journals for an interest in ancient Egypt so passionate that it was ‘a form of adultery with him’. He died when his son was eleven, and his wife and her second husband (the drama critic Henri Gouquier) sent the boy to boarding school. At about this time young Feydeau first became fascinated by theatre, and – like his near contemporary Alfred Jarry – wrote skits and sketches to amuse his school friends.

From 1883 Feydeau worked as secretary to the Renaissance Theatre, and his first full-length play, Tailleur pour dames (1887), had a successful run there when he was twenty-five. At about the same time he met and married an heiress, and in 1892 he had a hit with Monsieur chasse! at the Palais-Royal, the theatre which had previously seen Labiche’s greatest triumphs. In the same year, Champignol malgré lui opened at the Nouveautés, and it and Tailleur pour dames each ran for more than 1000 performances. Feydeau went on to write more than two dozen plays, ranging from one-act sketches to historical spectaculars, and including the grands vaudevilles for which he is best known outside France: these range from Un Fil à la patte in 1894 to his mature masterpieces L’Hôtel du libre échange, Le Dindon, La Dame de chez Maxim and La Puce à l’oreille.

Feydeau’s public success was offset by private misery. He spent each afternoon writing or directing, each evening at the show and then at Maxim’s (where he had a table permanently reserved); he returned home at three or four in the morning, and began again at noon the next day. His wife shared none of his interests, and eventually asked him to leave. He gambled on the stock exchange, and lost not only the fortune his plays earned but also his valuable art collection. In 1909 he moved to a suite in the Hôtel Terminus (near the Gare St Lazare), and spent ten years there, dividing his time between the theatre, Maxim’s and a succession of whores, from one o

f whom he contracted syphilis. He stopped writing in 1916; in 1919 he announced that he was Napoleon III, and was committed to an asylum; he died in 1921.

This private anguish is occasionally reflected in the plays. A bitter or bilious note sometimes darkens the hilarity, and collapsing marriages and lonely bachelors are treated with more savagery than the plots seem to warrant. But it hardly impinged on his dazzling public success. He was the most successful dramatist of his generation in France, and regularly had two, three or even four plays running at the same time in Paris. He was an actor and a director whose stage business exactly matched the demonic ingenuity of his plotting and dialogue. By his death he was regarded as one of France’s major comic dramatists, a worthy successor to Molière and Labiche, and his work is still performed cyclically at the Comèdie Française, two different plays each year.

Feydeau’s style

Feydeau was a highly self-conscious stylist. He learned his craft as a schoolboy by writing parodies and imitations of authors he admired, and in later life often wrote scenes and sketches simply as stylistic exercises. He analysed the work of his great forebears and successful contemporaries, borrowing – in a way which can easily be traced – a plot-inflexion here, a type of scene there, a turn of phrase or business somewhere else. Until the late 1890s he regularly worked with collaborators, in the manner favoured by all comic dramatists of the time – not so much sharing the actuad writing, as honing ideas together before one or other set the results down on paper. (In Feydeau’s case the writing is clearly his own. Each collaborator’s role seems to have been mainly to give advice and approval, and in any case by the time of Le Dindon he was working, for preference, entirely on his own.)

Feydeau’s main sources were Molière, and through him the commedia dell’arte, Plautus and Terence. These provided a repertoire of characters and situations, and above all an attitude to society and human nature, which are the basic stock of farce. His gulled husbands, scheming servants, pompous military men and vacuous idiots may wear the clothes and follow the social conventions of the belle époque, but they come directly from this tradition. From Molière, especially, he learned the power of farce to make barbed social comment: he particularly admired Le Malade imaginaire and L’Avare.

One of the most fertile strands in Molière’s output, that of the comédie-ballet, had been devised initially as a court entertainment for Louis XIV. These works (Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme is typical) frame straightforward satirical farce with extravagant music numbers, often involving pantomime-like characters (such as genies and mad professors), and using an unlikely mixture of ballet skills and slapstick. This tradition was matched, in popular theatre, by the vaudeville, or voix de ville. This was satirical street entertainment, in which the manners and ideas of the pretentious were burlesqued in (often bawdy) verse set to popular tunes, and whose grotesque and slapstick action was sometimes – as in commedia dell’arte – totally unrelated to the words being said. In Britain, and later in the United States, the style evolved into ‘music-hall’ and ‘vaudeville’ respectively; the sketches were separated from the music-numbers (though both remained satirical) and the physical display was split between slapstick (for example drunk-scenes) in the sketches and displays of such skills as plate-spinning or eccentric dancing (and later, striptease) among the other items. In France, the vaudeville tradition was gentrified into a kind of pastoral opera with spoken dialogue (of which Rousseau, no less, wrote an early example), into operettas like those of Offenbach, and into farcical plays satirising the bourgeoisie, with interpolated songs set to popular tunes of the day.

Labiche was the great nineteenth-century master of this last form, and his An Italian Straw Hat (usually nowadays performed without the songs) is a characteristic example of the genre. He also perfected a kind of vaudeville without songs: plays using physical business and rapid crosstalk to satirise bourgeois manners of the time. They were called grands vaudevilles, and are the principal link between Molière and Feydeau, and the main influence on Feydeau’s style. In his grands vaudevilles, Labiche worked consciously to develop character: the puppet-like figures of An Italian Straw Hat are the exception in his work. The comedy is motivated by each character’s individuality as well as by the needs of the situation: obsession, irritation and obtuseness, and the misunderstandings they engender, motor every play.

Labiche’s plots – and Feydeau’s after him – were also crucially influenced by the then-current fashion for the ‘well-made play’. In this, the plot (usually in three acts) begins with an exposition which tells us the background history of the characters and also that there is a secret whose discovery will change all their lives. It starts at normal pace, but gathers momentum irresistibly until the first-act curtain comes down on confusion (often caused by revelation of the secret in question). There follows a series of quidproquos: mistakes, ironies, deceptions, misunderstandings, which always lead to a reversal of the hero’s situation, from heights to depths or vice versa. The third act then explores the way this reversal affects every other character, and tidies up loose ends. Thousands of serious ‘well-made plays’ were written in the late nineteenth century – Ibsen’s prose tragedies are outstanding examples – and the style was a main theatrical form in France, seen at its best in the plays of Augier, Becque and Sardou and of course the farces of Labiche. It was particularly valuable to farce-writers, as its discipline corseted the raucousness of vaudeville, allowing slapstick and hilarity to co-exist with a sustained satirical assault on bourgeois morality and convention.

Although Feydeau’s main debt is to Labiche, he also learned from three contemporaries in particular. Maurice Hennequin, in the 1870s and 1880s, had great success with lunatic-action farces, successions of non-sequitur dialogue and slapstick confrontation – the original ‘doors’ French farces and the models for many of Feydeau’s second acts (such as that of Le Dindon). Henri Meilhac, ‘the Marivaux of the boulevards’, and his collaborator Louis Halévy, wrote, among other things, the books for Offenbach’s mythological burlesques, and were masters of the difficult art of letting characters speak apparently airy, natural dialogue while actually articulating the most extravagant passions and bizarre ideas. Their scripts flow as evenly and seamlessly as Hennequin’s are unpredictable, and their influence can be seen particularly in Feydeau’s opening acts, and in the way he brings back dialogue-interest in his third acts, restoring of urbanity which, while never less funny, produces a welcome change of pace from the breakneck slapstick of the second acts.

Feydeau’s mastery of the conventions of the well-made play – not to mention his audience’s familiarity with the form – allowed him to ironise and parody both it and its component parts, to deal easily and farcically with subjects which, handled by serious dramatists at the same period, evoked howls of outrage and embarrassment. Impotence, for example, is a subsidiary theme in Act Three of Sauce for the Goose (where it arises, if that is the word, from Redillon’s sexual exhaustion) and it motivates the whole plot of A Flea in Her Ear (where, because Chandebise is impotent, his wife suspects – quite wrongly – that he is ‘spending himself’ with a lover). Another serious subject which runs through all the plays, to the point of obsession, is the status of women: their equality with men and their ‘power’ within society and especially within marriage and the household. Feydeau’s plots may revolve around adulterous intrigues (or, rather, would-be or mistakenly-suspected-to-be adulterous intrigues), but the meat of the plays is often the way a wife takes control, asserts her individual dignity, even sanity, in a lunatic world. Invariably, he gives his women more richness of character than his men; the men bluster, scheme and flail, while the women change and grow. This gives his plays a dimension lacking in other farces – even in such masterpieces as (in English) The Rivals or The Importance of Being Earnest – and links them with such later writers as Orton, who explores what might be called the condition of psychological anarchy, or Ayckbourn, in whose plays psychological inadequacy is a recurring

theme. It is the essence of farce that such serious matters – indeed any serious matters – should not obtrude, that silliness should rule. But audiences leave a Feydeau play sated in a different way from most other farces, and I believe one of the main reasons is the way he touches on the darkness in human life and the unpredictable obsession not only at the surface but deep down in human character.

Each of the plays included in these two volumes shows a different aspect of Feydeau’s art. Jailbird (Gibier de potence) is an early work, first performed in 1883, at a semi-private theatre club, organised by the twenty-one-year-old author and like-minded friends. It was one item in a miscellaneous programme of monologues, comic songs and daft poems; Feydeau himself directed and took the part of Plumard. The piece shows occasional apprentice touches: the inconsequentiality of some of the jokes, for example, climaxing in the very last line of all, suggests a group of students giggling together rather than a single-minded artist fully in control of his effects. But the themes of Feydeau’s major works are all here, and the misunderstandings and dazzle of the dialogue show his mastery even at this early age. In particular, the ‘unmasking’ scene and the scene where Lemercier and Taupinier try to outboast one another as assassins stand with his most lunatic, most felicitous inventions.

Plays 2

Plays 2