- Home

- Georges Feydeau

Plays 2 Page 2

Plays 2 Read online

Page 2

Pig in a Poke (Chat en poche) was first performed in 1888, a year after Feydeau’s first big ‘hit’, Tailleur pour dames. It is a masterpiece of construction, not so much an arch as continuous escalation of confusion – and the Meilhac/Halévy influence is especially noticeable, in that the characters’ apparently ordinary dialogue (the kind of language you might have heard in any drawing-room of the time) belies the astounding content of what the people are saying or the thoughts inside their heads. Examples of Feydeau’s scintillating stagecraft in this play are his careful, almost Ibsenish control over the escalation of the daftness in the first act, the counterpointing in Act Two of the Winstanley/Julie story with the main plot, and the way he keeps back the play’s major surprise, the Sistine Chapel business, until the last act, just when we might think that the comic possibilities of the situation had been exhausted. Pig in a Poke may be chamber music compared to the grand symphonic structures of A Flea in Her Ear or The Girl from Maxim’s, but it is also one of his most accomplished works.

Now You See It (Le Système Ribadier, written in collaboration with Hennequin in 1892), a darker comedy altogether, subverts the vaudeville tradition, even as it follows it, letting the men’s obsessions turn them into mechanistic puppets – in a manner English readers may associate with Orton’s characters in Loot or What the Butler Saw – while the heroine’s character and personality flower before our eyes. It has one of the smallest casts and tightest constructions of any Feydeau farce. It was one of the author’s own favourite plays and he revived it in 1909 under a new title, Nothing Known.

The One That Got Away (Monsieur chasse!, 1892) is a fine example of Feydeau’s ‘demented clockwork’ style of plotting, an effect much heightened by the smallness of the cast. Act One sets up a dozen criss-crossing situations, and shows us a group of people each of whom has something to hide from at least two of the others. Act Two brings all these people together in a situation where they should never, ever, meet, and is a frenzy of mistaken identities, mock-tragic dialogue and slapstick action involving doors, a closet, a double-bed, a man in underwear and a police chase. (Feydeau, who directed his own plays, always made his actors perform the dialogue of such scenes with utmost seriousness, as if they were high tragedy; the action, by contrast, was speeded up, heightened and mechanistic. Dislocation between the two styles made for hilarity – a production-method still followed in France, where Feydeau’s farces are performed in rotation at the Comédie Française, but curiously seldom observed in English-language productions, perhaps because our farcetraditions tend more towards the end of the pier in one direction or ‘high comedy’ in the other.) Act Three picks up all the dangling loose ends from Act Two, further twists them and then untangles them while at the same time resolving the ‘serious’ issues of the play: Duchotel’s infidelity and the suspicions of Léontine which set the action spinning in Act One.

Sauce for the Goose (Le Dindon), which enjoyed a long run at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in 1896, is a characteristically ‘well-made’ grand vaudeville, with a lunatic second act framed by gentler material. It is, however, driven by character. Each person is clearly individuated and the differences between Redillon and Potagnac or Lucienne and Clotilde make the point that two individuals can share the same approach to life, or the same response to unexpected events, but show it in entirely different ways. Both this play and Heart’s Desire Hotel (L’Hôtel du libre échange), which dates from two years earlier, make use of the hotel setting in order to create a space situated halfway between the private and the public, a space where desires which cannot be spoken of in a polite bourgeois salon emerge and press for satisfaction. Both plays make hilarious use of rooms with several doors, some of which allow for escape, while others lead only into cupboards or bathrooms. And both plays benefit from the sense that hotel guests have of being constantly observed, even spied on, by people they hardly know. Heart’s Desire Hotel is justly one of the most famous comedies of assumed identity in the repertoire; the fact that the only couple to achieve any satisfaction is the young Maxime and Victoire, while the older characters remain frightened and frustrated, is entirely in keeping with the traditions of farce going back to classical times.

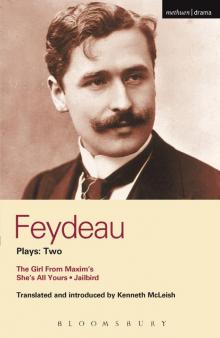

In most of Feydeau’s plays the characters are drawn from middle-class society, but the plot of The Girl From Maxim’s (La Dame de chez Maxim, Théâtre des Nouveautés, 1899) turns on a liaison – or rather two liaisons – between representatives of the respectable middle classes and a show-girl named ‘Shrimp’ (la môme crevette in Feydeau’s original). After a series of quidproquos, all set off as usual by the terrified attempts of the respectable married man to find a way out of the embarrassing situation his sex drive, combined with a lot of drink, has landed him in, it is the show-girl who saves the day by her cool-headedness and lack of personal pretensions. In this respect, both this play and She’s All Yours (La Main passe. Théâtre des Nouveautés, 1904) come close to the Naturalist plays of the period in which bourgeois hypocrisy, especially in sexual matters, was satirised in more serious dramatic form. The characters of She’s All Yours are recognisable people, who might be part of a play by Galsworthy. They are trying to come to terms with the modern world (as the play opens Chanal is trying to record a message on a phonograph) and the dilemmas into which they get themselves are at least partly due to their chronic inability to communicate with one another that recalls Chekhov.

Translation

Translating farce is risky. We are dealing not just with a foreign country, whose customs and manners are only superficially like our own, but with foreign slang, foreign preconceptions and foreign ideas of funniness. This is a major part of the appeal, but it can also give the plays, in translation, a kind of exotic, pseudo-literary gloss lacking in the original. Gogol’s The Government Inspector is a case in point. Its humour depends on a clear view of Russian small-town society at a particular moment in time, and the attitudes of people of that place and time to each other, to visitors, dignitaries and servants, are vital to the jokes. But to go at it head-on, to assume that the audience will know, or pick up, every nuance, would be to produce a play in English whose oddness baffled as often as it seduced. The results might be funny, but would weight the play in a way quite different from the original: it would become first and foremost a literary work, a critique, rather than a piece of straightforward stage entertainment. I have seen foreign-language versions of Ben Travers which unwittingly give the same impression. An alternative method of translation, regularly followed in Britain until the 1960s, is to resite the farce in a local setting, to English it. (In 1896 Now You See It was performed in Drury Lane in a version resetting it among the English aristocracy; in 1959 Coward similarly reworked Occupe-toi d’Amélie as Look after Lulu!) This process of adaptation sanitises the foreignness, but it can also choke the original motor of the humour, replacing the original preconceptions and ‘givens’ with notions from entirely another place and time.

In this volume, I have treated each of the plays slightly differently, though my purpose has been the same each time: to try to recapture the effect I think Feydeau was aiming at, in a form instantly understandable by modern English-speaking audiences. The translation of Sauce for the Goose is ninety-eight per cent meticulous. The first exception is the title. Le Dindon, to a French audience, means not only ‘the turkey’ but also the standard farce fall-guy, the character on whom every indignity is dumped – including, in this case, the reversal of fortune on which a ‘well-made’ play depends. Potagnac’s last line, in the original, is, ‘It was written [in the stars]: I’m the dindon’ – and so he is. The second exception is the characters of Brünnhilde and Soldignac. In the original they are English, and speak a kind of strangulated, invented English which must have been hilarious in 1890s France but doesn’t work in 1990s Britain. I began by giving them the kind of plum-in- the-mouth English we are used to in farce, but found that this made them more complex than the simple ‘volcanoes’ Feydeau had in mind, overbalancing their scenes. I

n the end I made them German, or rather cod-German, as fake as Feydeau’s original English.

Pig in a Poke combines farce and comedy of manners, and it seemed to me that a rigid but unspoken social framework ought to underlie the action. Although that of the original (bourgeois Paris of the belle époque) is remote from us, it is paralleled in Edwardian England, and I accordingly reset the play in Camberwell in 1909. Since this made nonsense of Pennyfeather’s original home (southern France), I transposed him first of all to Wales and then, because this hardly seemed exotic enough, to South America. The play also depends, in part, on the absurdities and pretensions of ‘polite language’ (which is constantly undercut by the basic situation); for this reason I slightly formalised my English, leaning a little towards the style of Pinero, Grundy, or other farce-writers of the period. When I began work on Now You See It, I took notice of Shaw’s criticism of the 1896 English production mentioned above. He said that the play would be strengthened if it were dovetailed from three acts to two, and if the action were ‘rotated’ so as to be seen from the wife’s point of view rather than those of the husband or lover. When I tried this, I found that it highlighted Feydeau’s exposition of her character, making its development central to the plot. I reinforced this by making Summersby (Ribadier in the original) not merely a pompous, hypocritical businessman but an MP working, officially at least, for female emancipation. I made Shaftesbury-Phipps (Thommereux in the original) come home from India, the British Empire, rather than from Batavia, the Dutch Empire. And finally, I replaced two tiny Feydeau characters, a maid and butler, with the invented character of Oriole. Satisfyingly, despite these shifts and redirections, it was possible to leave most of Feydeau’s original dialogue intact.

Kenneth McLeish, June 1993 (with additional material by David Bradby)

Translator’s note: the original French texts, prepared from the prompt script, were full of indications of the actors’ moves in the first production (‘he goes two steps up left’; ‘she sits’ and so on). I have pruned these to a minimum, keeping suggested blocking and business only when they seem integral to character or action.

Kenneth McLeish’s great passion was for comedy, and he delighted in the skills it demanded from everyone involved. He intended that these plays should be dedicated to all those professionals and amateurs who worked with him over many years to make people laugh. I am very grateful to David Bradby for his work in completing the introduction.

Valerie McLeish, 2000

The Girl From Maxim’s

La Dame de chez Maxim

Characters

Lucien Petypon, a society doctor

Gabrielle, his wife

Doctor Édouard Mongicourt

Étienne, Petypon’s servant

Shrimp, from the Folies-Bergère

General Petypon du Grelé

Lieutenant Marollier

Varlin, an insurance agent

Captain Corignon

Roadsweeper

Curé

Clémentine, the General’s niece, engaged to Corignon

Émile, the General’s batman

Chamerot, Guérissac, junior officers on the General’s staff

Dowager Duchess of Valmonté, an aged aristocrat

Duke of Valmonté, her son

Baroness, Madame Claux, Madame Ponant, Madame Hautignol, Madame Virette, a clan of provincial ladies, intent on good breeding

Vidauban

Madame Vidauban

Tournoy

Madame Tournoy

Lord Mayor

Lady Mayoress

Children, Firemen, Footmen, Officers, Porters, Wedding guests

The action takes place in the 1880s. Acts One and Three take place in Petypon’s Paris apartment, Act Two in the General’s château in Touraine.

Act One

Reception room of Petypon’s apartment. R, door to the hall; window, L, door to Gabrielle’s rooms. Centre back, slightly at an angle, large curtained archway leading to Petypon’s bedroom. The archway should be large enough for us to see the bed and other bedroom furniture. Onstage, the usual furniture: tables, chairs, armchairs, sofa, pouffe covered with a tablecloth, office desk, sideboard, bookcase. One other chair is brought in during the action: the ‘Ecstatic Chair’ (see page 53).

As the curtain rises, the stage is in darkness, so that we can’t yet see the fantastic disorder of the room, as if after a wild party. Doorbell, off. Pause. Then we hear voices in the hall.

Mongicourt (off) You’re joking. He can’t be.

Étienne (off) But he is, Monsieur.

Enter Mongicourt and Étienne.

Mongicourt (loudly) How can he be still asleep?

Étienne Not so loud, Monsieur.

Mongicourt (lower) How can he be still asleep?

Étienne It’s a mystery. He’s always up at eight, and it’s twelve already …

Mongicourt Fast living.

Étienne Pardon, Monsieur?

Mongicourt Not important.

Étienne I thought I heard Monsieur say ‘fast living’.

Mongicourt You know what that is.

Étienne Well, no, Monsieur. But I do know Doctor Petypon. A perfect gentleman – I’d trust him with my wife.

Mongicourt You, married?

Étienne Good heavens, no, Monsieur. And if that’s fast living, the way Doctor Petypon lives …

Mongicourt (interrupting) D’you think we could have some light in here? You can’t see a thing.

Étienne Of course, Monsieur.

He opens the curtains. The room is in chaos, the sofa overturned, chairs and tables all over the place. A squashed top hat; a collapsed umbrella.

Mongicourt and Étienne Oh!

Étienne What’s been going on?

Mongicourt Looks like an orgy.

Étienne But what was he doing?

Mongicourt Fast living.

Étienne H’m. If you ask me, drink was taken.

Mongicourt Étienne!

Étienne No, Monsieur. Not Doctor Petypon. All he drinks is soda water … with a dash of milk to settle his stomach.

Mongicourt (pointing to the pouffe) What on earth is that?

Étienne A pouffe, Monsieur. It’s temporary. Madame’s embroidering a cover. Till then, we’re using that tablecloth.

He fusses round the room.

What a mess!

He starts tidying. Mongicourt picks up the remains of the top hat.

Mongicourt Whatever’s this?

Étienne A hat, Monsieur.

Mongicourt Very stylish.

Étienne I don’t know what he was doing…

Mongicourt Never mind what he was doing. I need him. Now. Wake him up. It is twelve o’clock.

Étienne You’ll have to take the blame, Monsieur.

Mongicourt I’ll take it.

Étienne And it’ll have to be done by normal sounds.

Mongicourt Pardon?

Étienne Doctor Petypon insists, Monsieur. He hates it when people wake him up by, ooh, I don’t know, firing pistols.

Mongicourt I’m quite unarmed.

Étienne He likes to come to consciousness gradually. Humming would be good. D’you think we could hum for him, Monsieur?

Mongicourt If you say so.

Étienne Quietly at first, then gradually louder.

Mongicourt Any particular tune?

Étienne No, no. What about – ?

He hums ‘Frère Jacques’.

Mongicourt Why that?

Étienne Madame embroiders to it. I find it haunting.

Mongicourt Well, if you say so …

Étienne Quietly at first, Monsieur.

Mongicourt Yes, yes, whatever.

He and Étienne begin singing ‘Frère Jacques’. They start quietly, but end up shouting at the tops of their voices. After some time there is a deep groan. It is impossible to say where from.

Mongicourt Shh!

Étienne What is it?

Mongicourt Some kind of anim

al.

Étienne Ah. No. That’s Doctor Petypon. He’ll be waking up.

Mongicourt Thank God for that.

Petypon (invisible) Oh … oh … oh …

Mongicourt Petypon?

Étienne Monsieur?

Mongicourt Hey, Petypon.

Petypon (still invisible) Oh … oh … ergh?

Mongicourt Get up, for heaven’s sake.

Petypon (still invisible) What time is it?

Mongicourt (to Étienne) Just a minute. That wasn’t from the bedroom.

Étienne It seemed to be behind us.

Mongicourt (looking all around) Where are you?

Petypon (sulkily; still invisible) Where d’you think? In bed.

Mongicourt It’s coming from there.

Étienne I think you’re right.

They turn the sofa over. Petypon is revealed in shirtsleeves, tie unfastened, sleeping.

Mongicourt and Étienne Oops.

Mongicourt What are you doing down there?

Petypon opens his eyes, stares bleanly and yawns. They recoil.

Mongicourt What a stink of drink.

Petypon Don’t be ridiculous.

He turns over and goes back to sleep.

Mongicourt Hey, Petypon.

He slaps his feet.

Petypon Now what is it?

He sits up and bangs his head on the back of the sofa.

Ow. The bed’s caved in.

Mongicourt Ha!

He and Étienne right the sofa completely.

Petypon This is the sofa.

Mongicourt So it is – and look, you’re under it.

Petypon Under it? What d’you mean, under it? It is the sofa?

Mongicourt puts the sofa back over him.

Mongicourt Oh yes.

Petypon (struggling angrily) What are you playing at? Who planted this sofa here?

Mongicourt lifts a corner of the sofa.

Mongicourt God moves in a mysterious way…

Petypon Get it off me.

The sofa is lifted off. Petypon sits up on the floor.

Plays 2

Plays 2